Table of Contents

|

| Fig. 1. A pair of T. bhamoensis males engaged in competition. (Photo: Danny Lim) |

Introduction

The Thiania bhamoensis (Thorell, 1887) or the metallic blue jumper, is a popular choice as a fighting spider in South-east Asia as males are known to engage in fighting behaviour both in nature and under artificial situation (Rashid & Azirun 1992). Besides their fighting prowess, the T. bhamoensis get its common name from its beautiful iridescent green-blue colouration, males being bluer and females greener.

Name

Binomial: Thiania bhamoensis Thorell, 1887Common name: Metallic Blue Jumper

Synonym: Marptusa oppressa Thorell, 1892: 300, 474

Etymology: Species name ‘bhamoensis’ literally means ‘from Bhamo’, referring to a city in northern Burma (Myanmar) called Bhamo.

Biology of Thiania bhamoensis:

Agonistic behaviour in battle

Male jumping spiders often have a complex and extensive repertoire of agonistic behaviour. This aggressive fighting behaviour among T. bhamoensis is one of the most fascinating aspects of its biology. For T. bhamoensis, a total of 12 ‘major displays’ can be observed between a male-male interaction (Li et al., 2002):

Displays:

1: Hunched posture

2: Posturing with legs I arched

- Arched forelegs are held roughly perpendicular to the sides of the body, with the femur angled upward 30°.

3, 4: Legs I arched and elevated

5: Waving of arched forelegs

- Both male T. bhamoensis held a hunched posture with elevated forelegs, bent abdomen and waving forelegs.

6: Bent abdomen

- The abdomen of the spider is often twisted at the pedicel and shifted to the left or right of its cephalothorax.

- A close-up of male-male contest. Note the bent abdomen of the male T. bhamoensis (Fig. 2).

7: Flexing of abdomen up and down

8: Embracing opponent

- Two spiders would approach each other with forelegs arched/elevated and bring their laterally erect palps into contact for an embrace.

- Observe the palpal pushing between two male T. bhamoensis, with forelegs elevated and not touching.

9: Palpal pushing

- During the embrace, both spiders would use their laterally erect palps to push each other, in the attempt to move forward. This form of pushing is used to assess the relative size, strength and endurance of its opponent.

10: Grappling

- From the embrace position, both spider move forward and interlock their forelegs in a struggle.

11, 12: Stepping-to-the-side, forward and backward.

- Spiders charge at each other indirectly, where they would step a little to the left/right, front or back in the midst of charging.

Check out these spider fighting videos!

The videos are divided into three groups; each featuring different fighting styles between male T. bhamoensis. The first video 'Krauser's Punggol V Randy's Optometrist' is a very short fight between two male T. bhamoensis, but features clearly the 12 agonistic displays from the spiders in sequential order.

At times, spiders skip steps from the agonistic displays and jump straight into the fight. 'Randy's Toothache V Ricky's Freeze' is the next short video that focuses on the palpal pushing display of the spiders. Following up, 'Ura's Aso V Randy's Valtor' and 'Randy's Valtor V Krauser's Satsugai' are two other videos where palpal pushing and grappling are the dominant displays of these spiders.

'Jong's Porkchop V Randy's Cannon' features a short but dramatically fierce fight between the spiders. Finally, 'Buaya's Tomiko V Randy's Mentor' features a longer fight between the spiders, along with a 'Kampong styled' commentary of the owners.

Moulting

The video below features the moulting process of a T. bhamoensis.

From this video, 0:00-1:25 minutes shows how the carapace of the cephalothorax opens up and swings away from the body. During this process, T.bhamoensis's heart rate increases and haemolymph pressure doubles. This causes a redistribution of internal mass to increase the cephalothorax's weight by ~80%, and decrease the abdominal weight by ~30%. This expansion of the cephalothorax helps the old exoskeleton at the carapace area to split open first (Ramel, 2013).

From 1:25-3:20 minutes, the sides of the abdomen split, allowing T. bhamoensis to pull its body out of the old exoskeleton. Finally, from 3:20-8:34 minutes, the extraction of the legs and pedipalps occurs. Once the legs are free, they are regularly exercised, shown from the twitching actions, until the cuticle hardens into a new skeleton.

Prior to moulting, the T. bhamoensis, stops eating for a few days. During this period right up to moulting, it secretes a form of lubricating fluid between the old hard skeleton and the new cuticle. This dissolves the inner layers of the old cuticle to makes the whole exoskeleton weak and easy to escape from. Nutrients from the inner layer of the old cuticle is also being recycled.

Spiders are most vulnerable when they are undergoing moulting. Any disturbance or interference can cause improper moulting of their exoskeleton, affect their legs' alignment and eventually locomotion (Ramel, 2013). So if you happen to witness a spider in the process of moulting, do not disturb it! Even if it looks like it is having considerable difficulty in extracting itself from the old exoskeleton, 'helping' it pull off the remaining exoskeleton can have negative effects on the spider.

Mating behaviour

These videos below show the courtship dance of the male T. bhamoensis to woo the female.

A successful courtship display is followed by mating with the female, which from the video, is shown to be pretty intensive.

Courtship behaviour of a male T. bhamoensis starts off by extending its forelegs in vibration. As the male slowly approaches the female, he would initiate a ‘poking’ gesture at the female’s face. This is possibly to test the receptiveness of the female towards his advances. However, the main predictor of a male’s courtship success lies in the quivering frequency of his forelegs. A study by Chan et al. (2007) shows that the quivering frequency of a male T. bhamoensis has a more significant effect on female mate choice decisions than does the extension of the forelegs. Moreover, females’ eavesdropping on male-male contests does not indicate that the female would naturally favour the winner. The more important role in determining the female’s mate choice is by the courtship insistence of the male T. bhamoensis.

Nesting-building behaviour in females

|

| Fig. 3. The closely situated leaves of C. asiaticum allows T. bhamoensis to build nests. (Photo: Li et al.) |

In the natural environment, T. bhamoensis are usually found between a horizontal pair of green leaves in a nest, especially on the Crinum asiaticum (Spider lily) (Fig. 3). The C. asiaticum is a native in tropical Asia and is grown in parks and gardens for their aesthetic appeal. They have long, green leaves with wide blades and stalked white flowers. Due to the proximity of the leaves of C. asiaticum, T. bhamoensis build their nests between these spaces (Li et al., 2002).

|

| Fig. 4. A female's egg sac built between two leaves of C. asiaticum. (Photo: Li et al.) |

The eggs of T. bhamoensis are wrapped with many layers of woven silk sheet on the surface of the lower leaf (Fig. 4), and the egg sac is flattened (Li et al., 2002).

General characteristics for identification in the field and lab:

Distribution:

Myanmar (Burma), China, India, Krakatoa, Lao, Malacca, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nicobar Islands, Singapore, Sumatra, Vietnam

|

| Fig. 9. World distribution of T. bhamoensis (highlighted in orange). (Image Source: Worldwide database of jumping spiders) |

Distribution in Singapore

T. bhamoensis is a relatively common species in Singapore and can be found in various residential areas, parks, gardens and forested areas. This spider species is well adapted to the urban environment of Singapore, and the ability to integrate into the urban landscape partly explains its success as a species to be found around the whole island. T. bhamoensis is the only species of its genera present in Singapore. There are a total of 17 species of genus Thiania worldwide (Song et al., 2002).

Man and spider: Serious business!

-As a sport

Spider fighting is a popular sport in Singapore and around the region too. Different spiders are used for fighting competitions in different parts of the world. In Singapore, the T. bhamoensis is the most widely used species (Li et al.,2002) Competitions most often involve two males in battle, although females of this species do fight too, and which the spider that wins the fight is titled ‘first king’ until it is replaced by another champion. This sport often involves betting and is one that is enjoyed by young and old.

-As a pet

|

| Fig. 10. (Photo: Arthur Anker) |

Fighting spiders are captured for their beautiful iridescent colours (especially the males) and nurtured to be future fighters in competitions. Spiders reared for fighting are sometimes fed by their trainers with his/her own secret formula to enhance its vigour. Moreover, prior to a fighting match, the spider is sometimes intentionally starved to increase its ferocity.

|

| Fig. 12. |

|

| Fig. 11. |

-As an inspiration

The practice of spider fighting in Singapore has led to a memoir entitled Spider boys by Ming Cher, and the production of popular local television series Fighting Spiders.

Classification:

AnimaliaArthropodaArachnidaAraneaeAraneomorphaeSalticidaeEuophryinaeThianiabhamoensis Thorell, 1887Taxonomy:

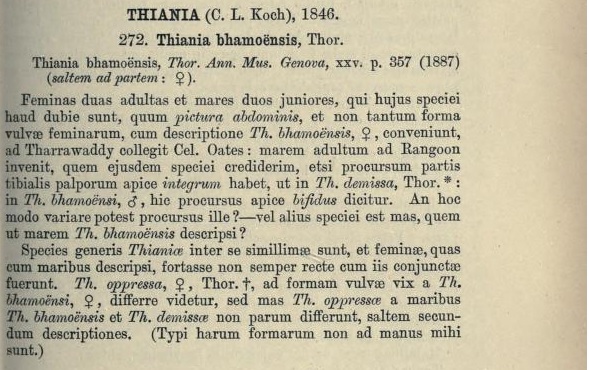

Formal description:

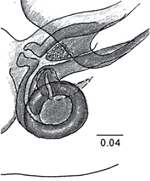

|

| Photo: Biodiversity heritage library |

Holotype: From Salticidae.org, the Holotype of T. inermis (Karsch in Lendl, 1897) is presumed to be identical with T. bhamoensis.However, this suggestion is not backed with further type information, so the information may prove invalid.

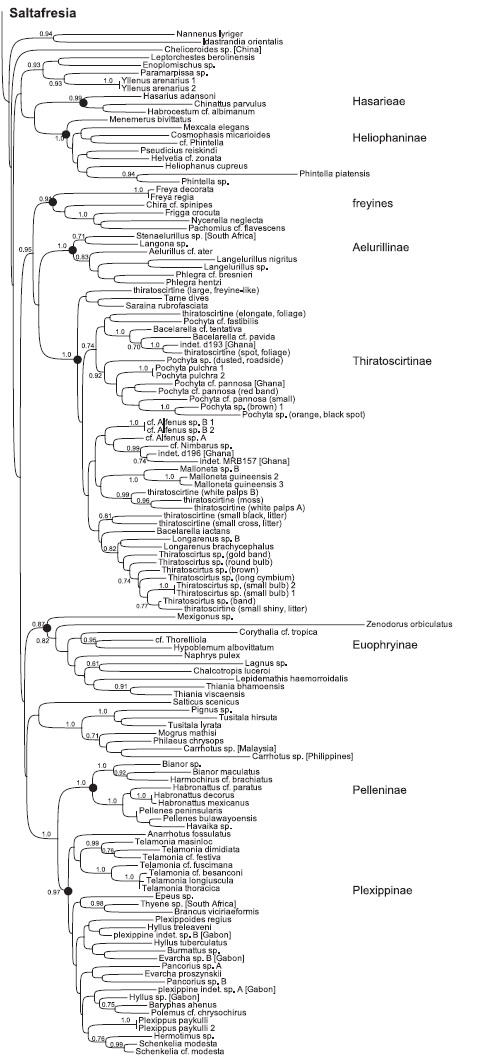

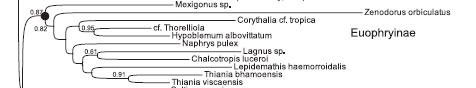

Phylogenetic relationship of salticid spiders using All Genes analysis :

|

| A closer look at Euophryinae. |

The 120 likelihood search replicates on the All Genes matrix yielded strongly concordant trees, and bootstrap values were high for many clades. From the phylogenetic tree, T. bhamoensis is in the same sister group as T. viscaensis, with high likelihood bootstrap proportion of 0.91 (Bodner & Maddison, 2012).

Inspired to rear your own fighting spider?

Where to find them?

This spider is synanthropic to some extent, and can be found in shrubs located around HDB estates, parks and gardens, forests and nature reserves. They are found on a variety of plant types; however, they most often are on spider lilies (Crinum asiaticum).How to catch a fighting spider?

By hand- This method is effective if you have steady hands and fast reaction time. An empty container can be slowly inched until it is above the fighting spider, then quickly covered. Often this requires some practice as jumping spiders can make a quick getaway.

By beating

- This method is the most violent of all. An overturned umbrella with a white background is preferably used. Place the umbrella below some shrubs, and start shaking the plants vigorously. This will cause your spiders to fall into the upturned umbrella, and it can be captured with a small container.

How to keep and care for your fighting spider?

In the past, fighting spiders were kept in little matchboxes due to their high availability. However, at present times, these spiders can be kept in plastic containers or pet containers instead, as matchboxes can be hard to find.

A more spider-friendly environment can be created within the plastic container by folding a leaf 'tent' for your spider pet. This video here shows a simple way to make a spider 'tent', Singaporean style!

When caring for your fighting spider, a few important items should be placed in the container to create a hospitable environment for your spider:

Water source

- Spiders need a moist enviromment or they would dehydrate and die off very quickly. Hence, always remember to place a water source in your container. This can be easily done by wetting a wad of tissue paper and placing it in one corner of the container. The tissue should be change regularly, as bacteria can accumulate on the wet surface and affect your spider’s well-being.

Ventilation

- Your jumping spider needs to breathe. Good airflow can help in healing your spider’s injury after a fight. If you are using a plastic container to store your spider, be sure to poke some holes on the lid to allow for air ventilation. Do not poke holes that are too large as your spider may squeeze out of them and wander away.

Substrate

- Leaves should be placed in the container as a refuge for your spider. To reduce the hassle of changing plant leaves from your spider container too often, leaves should be collected with the stem intact, and placed in a small container of water, with cotton wool wrapped around the stem-cut.

Sunlight

- Your spider container should have access to sunlight. Sunlight is important in maintaining the iridescent colours on your spider. However, at night, your spider also needs to be exposed to periods of darkness to rebuild their photoreceptors (Locke, 1980).

Food

- Fighting spiders need not be fed regularly, and can be done every 3-4 days. The Thiania bhamoensis eats a variety of live insects such as fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), mosquitoes, mealworms and common houseflies. Flies can usually be caught from the surrounding with a net. However, if you need larger quantities of fruit flies for your fighting spiders, a tip is to buy a bunch of bananas and allow it to ripen in an open space in your house. As the bananas ripen, it will attract more fruit flies, which can be easily caught with your net. As the saying goes, ‘Time flies like an arrow, fruit flies like a banana’.

This short video below features a spider (Thiania subopressa) preying on a mealworm by pouncing on it.

Spiders as pets?

Spiders may not be conventional pets, especially not in Singapore. According to the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore, the import of spiders and insects as pets into the country is considered illegal (AVA, 2013). However, there are no restrictions of having spiders from Singapore as pets.

With that being said, readers should still practice caution and insight when rearing fighting spiders. Despite the commonality of T. bhamoensis, readers, especially spider hobbyists, are not encouraged to catch large numbers of fighting spiders, as this may upset the micro ecosystems within an area. If large quantities of spiders needs to be caught, one must apply for a permit with NParks stating the objective of their collection (e.g. student experiment, spider ecology assessment etc.).

Large spiders such as tarantulas, which can be easily bought from neighboring countries should not be brought into Singapore. This is because a foreign species may bring with them diseases or may unbalance the native's ecosystem by competing with native spider species for resources.

However, catching fighting spiders and observing its fighting behaviour can always be a learning experience, as well as bringing back memories of simpler times, when smartphone games and videos were not yet the obsession. By observing the actions and behaviour of the T. bhamoensis, one becomes a step closer to nature.

Glossary

Agonistic behaviour: Any form of behaviour associated with aggression, including threat, attack, appeasement or flight. It is often associated with defense of territory.

Author: The person to whom a work, a scientific name, or a nomenclatural act is attributed. For example,for Thiania bhamoensis Thorell, 1887, Thorell is the author of Thiania bhamoensis and the scientific name was made official in 1887.

Binominal name: The combination of two names, the first being a generic name and the second a specific name, that together constitute the scientific name of a species.

Carapace: The hard dorsal covering of the cephalothorax.

Cephalothorax: The anterior of the two major sections into which the body of a spider is divided, comprised of a fused head and thorax.

Female eavesdropping: The acquisition of visual information about the potential mates from male agonistic interactions.

Femur: The third segment of a spider's leg (from the body).

Moulting: The shedding of the exoskeleton to allow for further growth.

Palp/ Pedipalp: The appendage anterior to the legs. In males, they are used to transfer sperm to a female.

Photoreceptor: Any biological structure that responds to incident electromagnetic radiation, particularly visible light.

Synanthropic: An organism that benefits from environmental modifications made by humans to such an extent that it becomes closely associated with humans.

Synonym: Each of two or more names used to denote the same taxonomic taxon.

Useful Links

1. http://www.jumping-spiders.com/

2. http://www.peckhamia.com/salticidae/

3. http://www.earthlife.net

4. http://www.findaspider.org.au

References

Allaby M. (2004). A Dictionary of Ecology, Synanthrope, (Retrieved: November 26, 2013).http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O14-synanthrope.html

AVA, (2013). Import, Export and Transshipment of Pets- Personal, (Retrieved: November 26,2013). http://www.ava.gov.sg/AnimalsPetSector/ImportExportTransOfAnimalRelatedPrd/PetsPersonal/

A Dictionary of Biology, (2004). Agonistic Behaviour, (Retrieved:November 26, 2013). http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O6-agonisticbehaviour.html

Atkinson R, (2009). Nervous and Sensory systems of Spiders, (Retrieved: November 14, 2013).

http://www.findaspider.org.au/info/spiderNS.htm

Bodner MR, Maddison WP (2012). The biogeography and age of salticid spider radiations (Araneae: Salticidae) from Canada. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65: 213-240

Cammack R et al., 'Photoreceptors', Oxford Dictionary of Biochemistry, answers.com (Nov 26 2013)

http://www.answers.com/topic/photoreceptor

Chan JPY, Lau PR, Tham AJ (2008). The effects of male-male contests and female eavesdropping on female mate choice and male mating success in the jumping spider,Thiania bhamoensis (Araneae: Salticidae) from Singapore. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 62: 639-646

Cohen JA, Weiner S, (2004). Glossary (Electronic field guide to Arachnids) from Brandeis University, (Retrieved: November 26, 2013)

http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/fieldbio/arachnids_cohen_weiner/glossary.html

ICZN, (2013). Glossary,(Retrieved: November 26, 2013).

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/hosted-sites/iczn/code/index.jsp?booksection=glossary&nfv=true#abbreviations

Li D, Seow HY, Seah WK (2002). Rivet-like nest building and agonistic behaviour of Thiania bhamoensis, an iridescent jumping spider (Araneae: Salticidae) from Singapore. Raffles Bull Zool, 50:143–151

Locke M, (1980). Insect Biology in the Future VBW 80. From Elsevier, pp.723 (Retrieved: November 14, 2013) http://books.google.com.sg/booksid=cNK4xyejWuAC&pg=PA723&lpg=PA723&dq=Blest+and+Maples&source=bl&ots=g2Lu7vFS5N&sig=GSZp6P3DTi1xW22zEAuuqEiMk0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=8MGVUuyzHMeVrgee8IBA&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Blest%20and%20Maples&f=false

Proszynski J, Deeleman-Reinhold CL (2010). Description of some Salticidae (Araneae) from he Malay Archipelago. I. Salticidae of the Lesser Sunda Islands, with comments on related species from The Netherlands, Arthropoda Selecta, 19(3): 153-188

Proszynski J, (2000). Thiania inermis,(Retrieved: November 26, 2013) http://salticidae.org/salticid/diagnost/thiania/inermis.htm

Ramel G, (2013). Spider Ecology from Earthlife, (Retrieved: November 14, 2013) http://www.earthlife.net/chelicerata/s-ecology.html

Rashid, NY, Azirun MS, (1992). Agonistic behaviour of male fighting spiders (Thania bhamoensis) from Malaysia. Nature, 17: 121-123.

Song DX, Zhang JX, Li D, (2002). A checklist of Spiders from Singapore (Arachnida: Araneae) Raffles Bull Zool, 50(2): 359-388

THORELL, T.,1887 Viaggio di L. Fea in Birmania e regioni vicine. II. Primo saggio sui ragni birmani.Ann.Mus.Civ.Stor.Nat. from Genova. Genova. 25: 5-417.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to Randy for his videos of Thiania bhamoensis which also show the quirks of rearing them as pets, as well as his unbounded enthusiasm in fighting spiders.